Thigh Pain Treatments

HAMSTRING STRAIN

Hamstring strains are common amongst sprinters, long jumpers, and hurdlers, as well as in sports where hard sprinting is required, such as football or hockey, and aging increases the risk. Most of the injuries occur in the biceps femoris muscle, especially during sprinting. Injuries

Hamstring strains are common amongst sprinters, long jumpers, and hurdlers, as well as in sports where hard sprinting is required, such as football or hockey, and aging increases the risk. Most of the injuries occur in the biceps femoris muscle, especially during sprinting. Injuries

occur just before foot strike. Hamstring tendinitis can occur at either end of the three muscles where the hamstring tendons attach to the bone.

Quick Contact

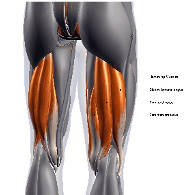

The hamstrings are comprised of three posterior thigh muscles: semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris, and they span the thigh from the ischial tuberosity at the bottom of the pelvis, to attach below the knee. They connect by tendon to the tibia and fibula below the knee and ischial tuberosity. At the top (proximal), the hamstrings attach to the bottom of the pelvis at the ischial tuberosity. The odd man out is the biceps femoris, where only one head attaches to the ischial tuberosity and the other head attaches to the femur. For this reason, the rectus femoris tends to be injured the most frequently. The hamstrings extend the hip and flex the knee, and while they are not active in normal walking or standing, they come into their own in running, jumping, and climbing. Athletes depend on healthy, well-conditioned hamstrings.

There are three grades of strain:

- Grade I: Minor strain with some pain, though the individual may be able to continue sport. Use ice, compression bandage, and massage, and get assessed by a sports physio – you may need to rest from sport for up to three weeks. With grade I, gentle jogging at seven days is fine, and fast sprinting by three weeks.

- Grade II: There is immediate pain which is more severe than the pain of a grade I injury, and it is confirmed by pain upon the stretch and contraction of the muscle. It can be also felt with a ‘ping’ feeling, like elastic in the muscle. You may be out of your sport from four to six weeks depending on the treatment you receive.

- Grade III: Hamstring strain is a severe injury. There is an immediate burning or stabbing pain and the athlete is unable to walk without pain. The muscle is completely torn and there may be a large lump of muscle tissue above a depression where the tear is. You will need crutches or sticks to walk initially, then when walking any distance, and you may need to take up to three months off the aggravating activity. Three months of sports rehab, massage, and treatment will be needed, and surgery if severe.

After a few days with grade II and III injuries, a large bruise may appear be-low the injury site, caused by the bleeding within the tissues. Grade III will need intensive icing every two hours for twenty minutes, elevate, rest, and a compression bandage. After about five days, you can start active rehab.

With all grades, as soon as pain permits, it is important to begin a prescribed program of stretching and range-of-motion exercises. Your sports therapist/physiotherapist will help you avoid prolonged inactivity resulting in muscle shrinkage (atrophy) and scar tissue (fibrosis). Excessive scar tissue is incompatible with healthy muscle function, and atrophy and scarring (fibrosis) are best avoided or reduced by prescribed exercise and stretching early in the rehabilitation process. This can be followed by massage and shockwave, then a graded rehab program return to sport encourages the tissue to stay pliable.

Rehab needs to include sprinting, as the hamstrings work hard to decelerate the lower leg as it swings out. It is in this phase – just before the foot hits the floor – that the hamstrings have to remain injury free, as they are maximally activated at maximum length.

As strength returns, resistance exercise is increased and Therabands can be useful. This is closely followed by core work. Fit ball work is great for stability, as both the trunk and pelvis get more stable, and sporting drills can follow the core stability training.

There are three grades of strain:

- Grade I: Minor strain with some pain, though the individual may be able to continue sport. Use ice, compression bandage, and massage, and get assessed by a sports physio – you may need to rest from sport for up to three weeks. With grade I, gentle jogging at seven days is fine, and fast sprinting by three weeks.

- Grade II: There is immediate pain which is more severe than the pain of a grade I injury, and it is confirmed by pain upon the stretch and contraction of the muscle. It can be also felt with a ‘ping’ feeling, like elastic in the muscle. You may be out of your sport from four to six weeks depending on the treatment you receive.

- Grade III: Hamstring strain is a severe injury. There is an immediate burning or stabbing pain and the athlete is unable to walk without pain. The muscle is completely torn and there may be a large lump of muscle tissue above a depression where the tear is. You will need crutches or sticks to walk initially, then when walking any distance, and you may need to take up to three months off the aggravating ac-tivity. Three months of sports rehab, massage, and treatment will be needed, and surgery if severe.

After a few days with grade II and III injuries, a large bruise may appear be-low the injury site, caused by the bleeding within the tissues. Grade III will need intensive icing every two hours for twenty minutes, elevate, rest, and a compression bandage. After about five days, you can start active rehab.

With all grades, as soon as pain permits, it is important to begin a prescribed program of stretching and range-of-motion exercises. Your sports therapist/physiotherapist will help you avoid prolonged inactivity resulting in muscle shrinkage (atrophy) and scar tissue (fibrosis). Excessive scar tissue is incompatible with healthy muscle function, and atrophy and scarring (fibrosis) are best avoided or reduced by prescribed exercise and stretching early in the rehabilitation process. This can be followed by massage and shockwave, then a graded rehab program return to sport encourages the tissue to stay pliable.

Rehab needs to include sprinting, as the hamstrings work hard to decelerate the lower leg as it swings out. It is in this phase – just before the foot hits the floor – that the hamstrings have to remain injury free, as they are maximally activated at maximum length.

As strength returns, resistance exercise is increased and Therabands can be useful. This is closely followed by core work. Fit ball work is great for stability, as both the trunk and pelvis get more stable, and sporting drills can follow the core stability training.

HAMSTRING TENDINITIS

Hamstring tendinitis can occur at either end of the three muscles where the hamstring tendons at-tach to bone. The ham-strings are comprised of three posterior thigh muscles: semimembra-nosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris, and they span the thigh from the ischial tuberosity at the bottom of the pelvis, to attach below the knee. They connect by tendon to the tibia and fibula below the knee and ischial tuberosity. At the top (proximal), the hamstrings attach to the bottom of the pelvis at the ischial tuberosity. The odd man out is the biceps femoris, where only one head attaches to the ischial tuberosity and the other head attaches to the femur. For this reason, the rectus femoris tends to be injured the most frequently. The hamstrings extend the hip and flex the knee, and while they are not active in normal walking or standing, they come into their own in running, jumping, and climbing. Athletes de-pend on healthy, well-conditioned hamstrings.

Hamstring tendinitis can occur at either end of the three muscles where the hamstring tendons at-tach to bone. The ham-strings are comprised of three posterior thigh muscles: semimembra-nosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris, and they span the thigh from the ischial tuberosity at the bottom of the pelvis, to attach below the knee. They connect by tendon to the tibia and fibula below the knee and ischial tuberosity. At the top (proximal), the hamstrings attach to the bottom of the pelvis at the ischial tuberosity. The odd man out is the biceps femoris, where only one head attaches to the ischial tuberosity and the other head attaches to the femur. For this reason, the rectus femoris tends to be injured the most frequently. The hamstrings extend the hip and flex the knee, and while they are not active in normal walking or standing, they come into their own in running, jumping, and climbing. Athletes de-pend on healthy, well-conditioned hamstrings.

It will hurt to stretch, pull, and sprint, and it can follow an unhealed tear or repetitive overuse. Your sports therapist will advise on RICE, stretching, and strengthening, and advice on a full rehab program is important. Massage and shockwave will also help to reduce scar tissue. Occasionally, hamstring syndrome occurs, where fibrous adhesions irritate the sciatic nerve as it passes above the ischial tuberosity. If shockwave cannot help, surgery may be needed.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and ultrasound scan, and treatment can include: RICE, shockwave, and strengthening and stretching with massage.

Do you have pain inside your hip or pelvis, or up to your back? When lifting your knee or stretching your hip, does it gets worse?

If so, you may have ischiogluteal bursitis.

ISCHIOGLUTEAL BURSITIS

The ischiogluteal bursa sits between the ischial tuberosity, at the base of the pelvis, and the hamstring muscles. It mimics hamstring problems – similar to hamstring tendonitis – and may come on after a lot of sprinting. Once a bursa becomes swollen and inflamed, it can make it difficult to move the joint, and a tell tale sign of bursitis is worsening symptoms after massage, and improvement with cooling. A common cause is a fall, and occasionally crystal deposits due to gout or infection.

Provisional diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, and for conformation, MRI, and treatment can include: rest from the aggravating activity, physiotherapy, and pulsed shortwave.

Have you had an injury to your upper anterior thigh that hasn’t got better?

If so, it could be a quads strain at the attachment onto the pelvis.

QUADS STRAIN (NEAR HIP)

The rectus femoris central tendon inserts at the pelvis in two locations, the direct and the indirect head. The indirect head is deeper, and flattens and rotates before it blends into the rectus femoris muscle at the central tendon. Injuries in this area are thought to occur due to the two parts acting independently, resulting in a shearing at the central tendon. Symptoms can eventually become apparent months after the injury, and recovery time with a comprehensive rehab program can be three to six times longer than a normal quads muscle strain.

The rectus femoris central tendon inserts at the pelvis in two locations, the direct and the indirect head. The indirect head is deeper, and flattens and rotates before it blends into the rectus femoris muscle at the central tendon. Injuries in this area are thought to occur due to the two parts acting independently, resulting in a shearing at the central tendon. Symptoms can eventually become apparent months after the injury, and recovery time with a comprehensive rehab program can be three to six times longer than a normal quads muscle strain.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, with MRI to confirm, and treatment can include: RICE, massage, physiotherapy, shockwave, and prescribed exercise and stretching.

Has the belly of your quads felt tender and weak for a long time, and has it been painful to run and kick?

If so, you may have quadriceps strain.

QUADRICEPS STRAIN

The quads comprise of four muscles: rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis. These muscles cause hip flexion and knee extension, and they arise from the pelvis and femur (thigh bone) and insert via the patella tendon on the tibia (shin bone). Only the rectus femoris attaches above the hip joint into the pelvis, and as a result, is far more vulnerable to injury.

Strains are graded in the usual way: mild, moderate, and complete tear. The usual symptom is immediate pain, and depending on the severity of the strain, swelling and bruising can also occur. The location of the injury can sometimes be felt – a complete tear may feel like a hole.

It is important not to stress the area and to control swelling as quickly as possible. The injury will heal in time – typically in two to six weeks, depending on the severity of the injury. Management of the scar tissue formation is important to regain full capability. In some cases, a strain can occur deep in the rectus femoris muscle, which will require significantly longer rehab.

Diagnosis is by sports physiotherapy assessment, and MRI if severe, and treatment can include: RICE, maintaining exercise by cycling (if not painful), sports massage, ultrasound, laser, and sports specific rehab.

Have you felt a sudden onset of pain – possibly a swelling in your thigh – most likely after a sprint start, rapid change of direction, jumping, or martial arts kick? Have you had traumatic pain to your inner thigh, and if you try to close your legs against resistance, is it too sore?

If so, you may have adductor longus strain, or rider’s strain.

ADDUCTOR LONGUS STRAIN

The adductors are located on the inside of the thigh and act to close the legs together. Adductor longus strain is common in football, hockey, tennis, horse riding, and karate, and it tends to happen when the athlete needs to quickly change direction and the adductors are subjected to high forces, such as in a football tackle where an adducting foot is about to kick the ball and meets an opponent’s leg. This type of strain is responsible for 62% of groin injuries.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and treatment can include: physiotherapy, shockwave, massage, and if acute, ultrasound and pulsed shortwave. Recovery can be lengthy – up to five months.

Have you had a bruising injury some months ago? Do you now feel a bony lump there?

If so, you may have myositis ossificans.

MYOSITIS OSSIFICANS

This is an uncommon condition in which bone is formed inside an injured muscle. Many sports are prone to muscle injury – such as football, rugby, martial arts, and hockey – and these injuries can lead to heavy internal bleeding, evident as bruising and swelling, and can also result in a blood clot, which is an ideal breeding ground for calcification. Left untreated, the calcification can continue to develop and may take over much of the injured site over several months.

The key to prevent myositis ossificans – or the growth of bone by calcification within the injured muscle – is to seek treatment as early as possible after the injury. Once formed, the bone can only be removed surgically and the current guidelines advise waiting up to 12 months to minimise the risk of further bone growth post-surgery. The cause of myositis ossificans is not understood, and there is a risk of further bone growth post-surgery.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, X-ray to confirm the diagnosis, and checks to confirm it is non-malignant. Treatment can include: drugs to relieve the symptoms, and surgery.

Have you suffered a blow to the front mid high (quads)? Are the muscles swollen and sore?

If so, you may have quadriceps contusion, or ‘dead leg’.

DEAD LEG

There are three grades of contusion, and grades I and II are commonly known as ‘dead leg’:

- Grade I: The thigh will feel tight and mildly uncomfortable on walking or extending the knee.

- Grade II: You will be unable to run or walk quickly, and unable to bend the knee fully.

- Grade III: A muscle tear with severe pain, you will be unable to walk without crutches or contract muscles. You will be out of competition for six to 12 weeks.

The quads comprise of four muscles: rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis. These muscles cause hip flexion and knee extension, and they arise from the pelvis and femur (thigh bone) and insert via the patella tendon on the tibia (shin bone). The quads are easily kicked in contact sports, sometimes leading to a severe bruise or tear (grouped as contusion) that can take weeks or months to heal. A quads contusion can be swollen, sore, and bruised.

A contusion injury results in a crushing force on your muscle tissue, and the body’s protective response is to wall-off the area of damage from the unaf-fected muscle in order to prevent damaging chemicals – released due to the injury – from further damaging more muscle. This results in an overall de-crease in the oxygen to the surrounding tissue. This walling-off causes stiff-ness, creating an internal splint to prevent further injury and slowing down healing. Repeated overuse causes microscopic soft tissue failure, inflammation, and rupture. Healing involves inflammatory cells, macrophages clearing necrotic cells, and muscle cells regeneration.

Treatment can include: physiotherapy, ultrasound, pulsed shortwave, light massage, and gentle prescribed rehab.

Do you have localised pain at the back of your thigh?

Does it hurt to bend your knee against resistance, and does it feel weak? Do your hamstrings feel tight when you stretch them?

If so, you may have hamstring strain.

THIGH PAIN DIAGNOSIS

Tight hamstrings, SI joint dysfunction, and lumbar spine radiculopathy all have to be assessed in order to confirm hamstring strain; just because the hamstrings may feel tight, they may not be short and therefore stretching does not always help. The brain feels tightness as a signal that something is wrong; it cannot perceive shortness in length. Therefore, overstretched muscles can feel tight, and the problem could be coming from the lower back, from the pelvis, or from the sciatic nerve. Back problems can cause short hamstrings and vice versa – lots of sitting or driving without core stability can cause this. You need to have a rehab stretching program specific to you and your sporting needs.

Tight hamstrings, SI joint dysfunction, and lumbar spine radiculopathy all have to be assessed in order to confirm hamstring strain; just because the hamstrings may feel tight, they may not be short and therefore stretching does not always help. The brain feels tightness as a signal that something is wrong; it cannot perceive shortness in length. Therefore, overstretched muscles can feel tight, and the problem could be coming from the lower back, from the pelvis, or from the sciatic nerve. Back problems can cause short hamstrings and vice versa – lots of sitting or driving without core stability can cause this. You need to have a rehab stretching program specific to you and your sporting needs.

Diagnosis is by sports therapist/physiotherapy assessment.

The hamstring muscles run down the back of the thigh, and there are three of them:

- Semitendinosus

- Semimembranosus

- Biceps femoris

They start at the bottom of the pelvis at a place called the ischial tuber-osity, crossing at the knee joint and ending at the lower leg. Hamstring muscle fibres join with the tough, connective fascia of the hamstring tendons attaching to bones. The hamstring muscle group helps you extend your leg straight back, as well as bending your knee.

During a hamstring strain, one or more of these muscles gets overloaded, and the muscles might even start to tear. You’re likely to get a hamstring strain during activities that involve a lot of running and jumping, or sudden stopping and starting. The three grades of hamstring injury are:

- Grade I: A mild muscle strain.

- Grade II: A partial muscle tear.

- Grade III: A complete muscle tear.

The length of time it takes to recover from a hamstring strain or tear will depend on how severe the injury is. A minor muscle pull (grade I) may take a few days to heal, whereas it could take weeks or even months to recover from a muscle tear (grade II or III).

Getting a hamstring strain is also more likely if:

- You don’t warm up before exercising.

- The muscles in the front of your thigh (the quadriceps) are tight as they pull your pelvis forward and tighten the hamstrings.

- You have weak glutes (bottom muscles). Glutes and hamstrings work together; if the glutes are weak, the hamstrings can be overloaded and become strained.

Treatment can include the following:

- Avoid putting weight on the leg as best you can. If the pain is severe, you may need crutches until it goes away – ask your doctor or physio if they’re needed.

- ICE: Ice your leg to reduce pain and swelling. Do it for 20 minutes every four hours for two to three days, or until the pain is gone. Compress your leg. Use an elastic bandage around the leg to keep down swelling. Elevate your leg on a pillow when you’re sitting or lying down.

- Take anti-inflammatory painkillers and painkillers from your pharmacist or GP. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) – like Ibuprofen or Naproxen – will help with pain and swelling. However, these drugs may have side effects, such as an increased risk of bleeding and ulcers. They should only be used short-term, unless your doctor specifically says otherwise.

- Practice stretching and strengthening exercises if your doctor/physical therapist recommends them. Strengthening your hamstrings is one way to protect against hamstring strain.

- Sports massage, shockwave, stretching, and rehab will all help to speed up recovery.

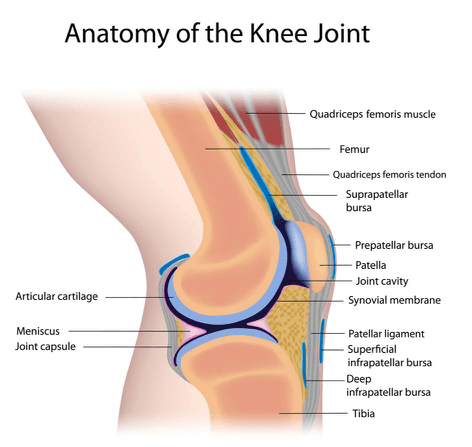

Are you unable to move your knee after a sudden trauma? Is the joint deformed, swollen, and cannot bear weight?

Are you unable to move your knee after a sudden trauma? Is the joint deformed, swollen, and cannot bear weight?

If so, you may have a dislocated knee.