Shoulder Problems

After an acute trauma, do you have severe pain with a ‘popping-out’ sensation in the shoulder?

If so, you may have a dislocated shoulder.

DISLOCATED SHOULDER

Shoulder dislocation is a very common traumatic injury that can occur across a wide range of sports. In 95% of cases it is an anterior (front) dislocation, where the head of the humerus (the upper arm bone) is forced forwards when the arm is turned outwards, and held out to the side (abducted). Posterior dislocation only accounts for 3% of cases.

Quick Contact

With a bankart lesion, the shoulder joint is particularly prone to dislocations due to its high mobility, and lack of stability. Dislocation can cause a labral tear – the labrum is a cup-shaped ring of cartilage, deepening the glenoid fossa into which the arm bone sits. There can be a lot of damage to soft tissue after dislocation.

Provisional diagnosis is by your physio, GP, and X-ray, and follow up treatment should include a time for immediate rest with a sling, then progressive physiotherapy mobilisations. Also, try soft tissue treatment for bruising with electrotherapy modalities and massage.

PECTORALIS MAJOR INFLAMMATION

The pectoralis major muscle is a large, powerful muscle at the front of the chest. We need this muscle to rotate the arm inwards, to pull a horizontal arm across the body, to pull the arm from above the head down, and to pull the arm from the side upwards. The weakest spot is where it inserts into the humerus. In weight training, the bench press is the most common reason for injury.

Provisional diagnosis is by a physiotherapy assessment, and treatment can include: initially, ice, and relative rest of the muscle. See a sports therapist or physiotherapist for massage, ultrasound, laser, and a rehab prescribed programme.

Do you have pain at the front of your shoulder? Does it hurt to lift a straight arm out in front of you?

If so, you may have one of the following conditions:

BICEPS LONG HEAD TENDINITIS

The biceps muscle splits into two tendons at the shoulder. The long tendon runs over the top of the humerus (arm bone), and the head attaches to the top of the shoulder blade. A rupture of this tendon is rare in young athletes, but common in older ones. Inflammation of this tendon is a fairly com-mon complaint, especially with swimmers, rowers, throwers, golfers, and weight lifters.

Provisional diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and ultrasound scan, and if tendonitis is confirmed, the treatment of choice can include: initially, relative rest, massage, sports therapy, stretching and strengthening exercises, and a full rehabilitation programme. Electrotherapy – such as pulsed shortwave can help reduce inflammation faster

If the patient is older or a partial tear is also seen on the scan, an orthopaedic opinion may well be needed. If the tendon goes on to tear, the surgeon will need to be consulted in case a repair operation is needed. Furthermore, if pins and needles (or numbness and weakness) are present, a full assessment of the cervical and peripheral nerves is needed.

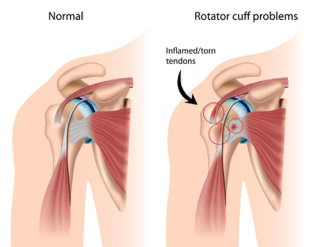

ROTATOR CUFF INJURY

Rotator cuff tendinitis describes the inflammatory response of one or more of the four rotator cuff tendons, due to impingement or overuse, and leading to more and more micro-trauma that can then lead to a tendon rupture.

The inflamed thickening of the tendons often causes the rotator cuff tendons to become trapped under the acromion – like a carpet

stuck under a door – causing sub-acromial impingement. Failure to heal then leads to further damage, resulting in a tendinopathy. Early treatment of tendinitis, therefore, is necessary in order to prevent the development of more chronic and serious conditions.

Treatment can include: postural exercises to lessen the impingement and local electrotherapies, such as laser, ultrasound, deep oscillation, or MRT.

Do you have pain when lifting your arm sideways? Does it get worse against resistance?

If so, you may suffer from the following:

SUPRASPINATUS TENDINITIS

Contraction of the supraspinatus (SS) muscle leads to abduction (lifting up sideways) of the arm at the shoulder joint. It works so hard during the first 15 degrees of its arc, and beyond 15 degrees the deltoid muscle supports the abducting of the arm, helping out strongly. When you get inflammation of this tendon, it leads to supraspinatus tendinitis. You will get shoulder pain with movement from the inflammation, and pain at night, as well as weakness in the shoulder and arm. There is also the possibility of tenderness and swelling in the upper front part of the shoulder, and in some severe cases, a difficulty to raise the arm to shoulder level – a painful arc from 60 to 120 degrees.

I learnt some useful diagnostic shoulder tests from two shoulder surgeons, Roger Hackney and Vinod Kathuria, and the tests have rather strange names: Neer’s impingement, Hawkins-Kennedy, and the Empty Can Test, the latter of which indicates a problem with SS.

TREATMENTS FOR ROTATOR CUFF TENDINITIS

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are often prescribed for the management of acute inflammation, providing you have a strong stomach. Ice packs, gels, and creams – either NSAID or herbal – can help reduce pain and inflammation and should be applied to the painful area for 15 minutes at a time, at regular intervals throughout the day. Electrotherapy

– as in ultrasound, pulsed shortwave, deep oscillation, and laser – all help, as do gentle shoulder mobilisations, massage, and postural exercises. Sport-specific rehab exercises guide you back to full fitness.

The provisional diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, and a diagnosis of the degree of damage is carried out via an ultrasound scan.

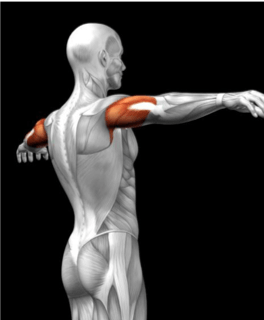

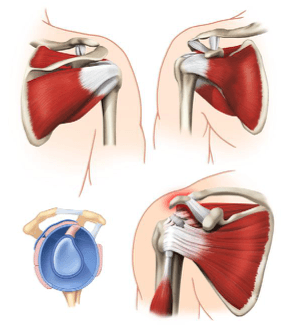

THE INTERPLAY OF SHOULDER MUSCLES

The supraspinatus is just one of four rotator cuff muscles, its partners in crime being infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. The infraspinatus is a thick triangular muscle, which occupies the chief part of the infraspinatous fossa (a sculptured dent in the back of the shoulder blade). As one of the four muscles of the rotator cuff, the main function of the infraspinatus is to externally rotate the humerus (backhand in tennis) and stabilise the shoulder joint.

The subscapularis is a large triangular muscle that fills the subscapular fossa (the front of the shoulder blade) and inserts into the lesser tubercle (bony knob) of the humerus, as well as the front of the capsule of the shoulder joint. The orthopaedic assessment will include specific tests to move the shoulder into specific positions in order to detect pain, indicating a tear. The name of these tests are the Gerber liftoff, the bear hug, and the belly press! There is no singular imaging device or technique available for a satisfying and complete subscapularis examination, but the combination of MRI and ultrasound scans work well, ultimately seeing it in surgery.

The rotator cuff muscles are a group of muscles that work together to provide the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint with dynamic stability, helping to control the joint during rotation. The scapula (shoulder blade) plays an important role in shoulder impingement syndrome. It is a wide, flat bone lying on the posterior thoracic wall that provides an attachment for three different groups of muscles – and it looks like the Star Trek Enterprise.

The subscapularis, infraspinatus, teres minor, and supraspinatus intrinsic muscles attach to the surface of the scapula and rotate the glenohumeral joint, along with humeral abduction (sideways). The extrinsic muscles include the biceps, triceps, and deltoid muscles, and these attach to the nobbly bits of bone called the coracoid process, the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, the infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, and the spine of the scapula. It’s as if these muscles all have their own coat hook, like in kid’s changing rooms, and these muscles are responsible for several actions of the shoulder joint.

THE SPORTY SHOULDER

The third group of muscles with funny names are mainly responsible for both the stabilisation and rotation of the shoulder blade. They are the trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and rhomboid muscles, and they attach to the medial, superior (upper), and inferior (under) borders of the scapula. Each of these muscles has their own role in shoulder function, and must be in balance with each other in order to avoid shoulder problems, like the tension on kite strings. Abnormal scapular (shoulder blade) function is called scapular dyskinesis.

The arm bone must be slid down and turned to avoid jamming up; the shoulder blade, during a throwing or serving, has to elevate the acromion process (the spoon-shaped bit overhanging the humerus head). If the scapula fails to properly lift the acromion, impingement may occur during the cocking and acceleration phase of an overhead activity. I see this a lot with my patients and describe it like the rubber stopper wedged under my door, stopping it from closing.

The two muscles most commonly inhibited/being lazy during this first part of an overhead motion are the serratus anterior and the lower trapezius. These two muscles act as a force couple within the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint to properly elevate the acromion process. If a muscle imbalance exists, shoulder impingement may occur, and this can usually be diagnosed by history and physical exam. During a physical exam, I twist or elevate the patient’s arm to test for reproducible pain (using the Neer sign and Hawkins-Kennedy test). These tests help localise the problem to the rotator cuff, however, the Neer sign may also be seen with subacromial bursitis, which is when the bursal sac gets inflamed and swollen, like a wet, thickened carpet jamming in the door.

You can inject lidocaine and a corticosteroid into the bursa – I used to in the hospital and I still do in my current clinic – and while it can be a quick fix, it is a very unpleasant injection to receive. If there is an immediately improved range of motion and a decrease in pain, this is considered a positive ‘impingement test’. It not only supports the diagnosis for impingement syndrome, but it is also therapeutic, and other treatments include electrotherapy, postural exercise, and dry needling.

Plain X-rays of the shoulder can be used to detect joint problems, including acromioclavicular arthritis, osteoarthritis, and calcification. However, ultrasonography, arthrography, and MRI must be used in order to detect any rotator cuff muscle pathology/problems. MRI is the best imaging test prior to arthroscopic surgery. Impingement syndrome is usually treated conservatively, but sometimes it is treated with arthroscopic surgery or open surgery. I have seen a lot of these operations, and they can be done with a local anaesthetic.

Non-surgical treatment includes rest from painful hobbies, as well as physical therapy and electrotherapy treatments to maintain a pain-free range of movement, improving posture and gaining a gradual pain-free strengthening of the shoulder muscles. As discussed before, in order to improve overall pain and function, treatment can also include joint mobilisation, Acupuncture, soft tissue therapy, therapeutic taping, rotator cuff strengthening, and rehab education regarding the cause and mechanism of the condition. TENS, deep oscillations, NSAIDs, and ice packs may also be used for pain relief. If nothing is helping and you do not have a muscle tear, then injections of corticosteroid and local anaesthetic may be used for persistent impingement syndrome. The total number of injections is generally limited to three, due to possible side effects from the corticosteroid.

I have watched Mr Hackney do this operation on several occasions, and also, on occasion, Mr Kathuria as well. A number of surgical interventions are available – depending on the nature of the pathology and the age of the patient – and surgery may be done arthroscopically (through a scope) or as open surgery. The impinging structures in the subacromial space may be widened by resection of the distal clavicle (the collar bone) and the excision of osteophytes (bony spikes) on the under-surface of the acromioclavicular joint. Damaged rotator cuff muscles can be surgically repaired, and this may be the only way a shoulder can function again. My mother had this surgery, and while she had a lengthy recovery, she also had excellent results.

Muscles attach to bone by tendons, and the inflammation of these tendons is called shoulder tendinitis, a type of tendinopathy. Tendinitis (also tendonitis) means the inflammation of a tendon, and the term tendinitis should be reserved for tendon injuries that involve acute injuries with inflammation.

Chronic tendinitis, chronic tendinopathy, or chronic tendon injury all refer to damage to a tendon at a cellular level (the suffix ‘osis’ means chronic degeneration without inflammation). Damage is caused by microtears in the tendon, and an increase in tendon repair cells. This may lead to reduced tensile strength. I remember Mr Hackney correcting me about tennis elbow – he said it is degeneration, not inflammation. He was referring to degenerative changes in the collagenous matrix, hypercellularity, hypervascularity, and a lack of inflammatory cells. The term tendonITIS (inflamed) is different to tendinOSIS (meaning wear and tear).

Corticosteroids are drugs that reduce inflammation, and they are injected along with a small amount of a numbing (haha) drug called lidocaine. They can make a tendon very weak; I used to fear a ‘twang’ sound after my injection as if one of my guitar strings were going, so I never carried out more than two jabs in any one tendon. Research shows that tendons are weaker following corticosteroid injections and far more likely to rupture.

By definition, anything that ends in ‘itis’ means ‘inflammation of’. Tendinitis is still a very common diagnosis, though research increasingly documents what is thought to be tendinitis and usually turns out to be tendinosis. Prof Gunn would say that the tendons get damaged due to an increased pull from muscle contractures, and that these muscle contractures present due to supersensitive nerves innervating them.

Tendinitis of the rotator cuff usually occurs over time, and it can be the result of poor posture, keeping the shoulder in one position – such as when on the computer – and not moving it over a period of time. You could be sleeping on the shoulder every night or having your arm bent up over your head. Or you could be doing a lot of activities that require extending the arm over the head at 90 degrees and above. Rotator cuff tendinitis can be developed from cleaning windows, painting ceilings, and manual jobs, as well as playing sports that require extending the arm over the head. This is why the condition may also be referred to as swimmer’s, pitcher’s, or tennis shoulder.

Often, we don’t know why rotator cuff tendinitis occurs, but mostly, over time you are able to regain the full function of the shoulder without any pain. It can affect one or more muscles in the shoulder, and without treatment, it can become a chronic problem.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, MRI, and ultrasound scan, and to reiterate, treatment can include: rest from painful activities, ice, sports therapy/physiotherapy, ultrasound, laser, massage, and progressive exercises for posture and muscle imbalance.