Knee Pain Treatments

What type of knee pain do you have?

This information is provided for guidance only and cannot be used as a diagnosis of your condition. It is designed to help you get some clarity about your problem, so you can discuss it further with an expert and obtain an accurate diagnosis.

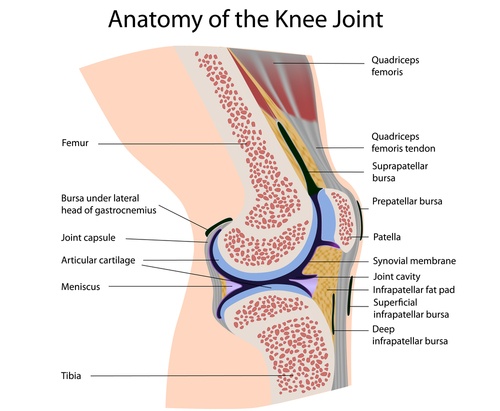

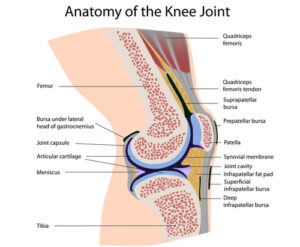

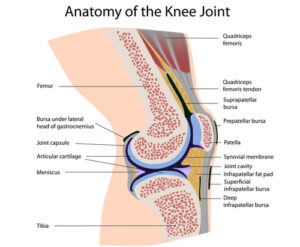

Anatomy of the knee

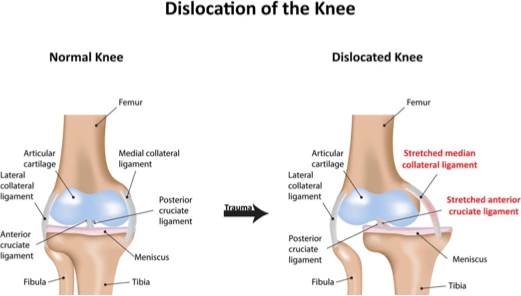

Dislocated Knee

Peroneal Nerve Injury

Medial Coronary Ligament

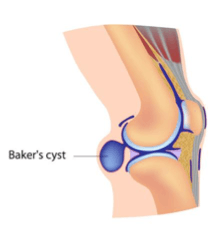

Popliteal Cyst

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Corticosteroids

Biological Agents

Supportive Treatment

Lifestyle Modifications

Physiotherapy

Surgery

Medial Meniscal Tear

Synovial Plica

Collateral Ligaments

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Knee Bursitis

Osteochondritis Dissecans

Suprapatellar Tendon

Chondromalacia Patella

Hypermobility

Infrapatellar Tendinitis

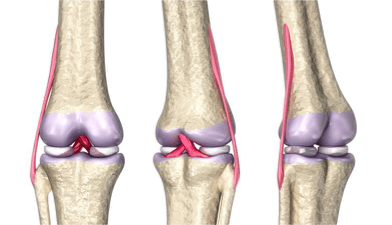

Collateral and Cruciate Ligament Combined Injury and Medial Meniscus Tears

Cruciate Ligaments ACL and/or PCL Sprain

Quick Contact

ANATOMY OF THE KNEE

DISLOCATED KNEE

This is a serious in-jury, and it describes the situation when the thigh bone (fe-mur) loses all con-tact with the lower leg bones (the tibia and fibula). For this to happen there is usually substantial damage to the tissues around the knee, often including complete tearing of the cruciate ligaments (ACL & PCL), plus damage to the collateral lig-aments and menisci, so it has the potential to cause significant damage to important vascular (blood) vessels and nerves. Immediate attention is re-quired as this injury can lead to the loss of the leg.

This is a serious in-jury, and it describes the situation when the thigh bone (fe-mur) loses all con-tact with the lower leg bones (the tibia and fibula). For this to happen there is usually substantial damage to the tissues around the knee, often including complete tearing of the cruciate ligaments (ACL & PCL), plus damage to the collateral lig-aments and menisci, so it has the potential to cause significant damage to important vascular (blood) vessels and nerves. Immediate attention is re-quired as this injury can lead to the loss of the leg.

After repositioning the knee, ongoing surveillance of the nerves and blood vessels may be needed, and due to the level of damage, surgical reconstruc-tion is usually required.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, X-ray, and MRI, with urgent medical attention needed. Treatment can include: having the joint repositioned by a medical practitioner, gentle progressive physiotherapy, having your blood vessels and nerves monitored, thorough rehab for mobility, balance, and strength, and possible surgery.

Did you have a blow to the outside of your knee? Is your foot weak when you lift it to walk?

Do you have a tingling/numbness on the outside of your leg?

If so, you may have peroneal nerve injury or radiculopathy (see spinal section).

PERONEAL NERVE INJURY

The peroneal nerve branches off from the sciatic nerve and is responsible for innervating the muscles that raise the foot and toes. Damage to the nerve can thus lead to spontaneous foot drop or weakness in lifting the foot. Other symptoms include a tingling or numbness on the outside of the lower leg, and pain down the shin or the top of the foot.

Diagnosis is by EMG tests, orthopaedic surgeon, or a back specialist.

Peroneal nerve injuries have a poor chance of recovery, worsening with time, so it is cimportant to be assessed quickly by a specialist who can determine whether to proceed with surgery or go down a more conservative route – typical conservative options include physiotherapy and orthotics.

Did you have a sudden onset of localised acute pain on the inner side of your knee, which is painful after a twisting injury and is still mildly painful when touched?

Did you have a sudden onset of localised acute pain on the inner side of your knee, which is painful after a twisting injury and is still mildly painful when touched?

If so, you may have a medial coronary ligament.

MEDIAL CORONARY LIGAMENT

The top of the shin bone (tibia) has a coating of cartilage, with two meniscal cups for the long thigh bone (femur) to move in. The medial meniscus is attached at the medial, lower edge to the tibia by the medial coronary ligament, and the lateral meniscus is attached at the lateral, lower edge to the tibia by the lateral coronary ligament. These ligaments act to stabilise the menisci and help limit knee rotation injury to the coronary ligaments.

Injury is most likely to occur with sudden, sharp direction changes, especially when the foot is planted securely, forcing a rotation of the lower leg (tibia) relative to the thigh (femur). Such injuries are common in football, rugby, tennis, squash, dancing, and martial arts, and aggravating factors include poor biomechanics and laxity in the four major stabilising knee ligaments (ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL). Injury can be from acute trauma – which normally causes immediate, sharp pain – or chronic overuse, such as from long distance running.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and possibly scope, and the medial coronary ligament usually heals conservatively.

Do you have a golf ball-shaped swelling at the back of your knee?

If so, you may have a popliteal cyst.

POPLITEAL CYST

This is also known as a baker’s cyst. Irritation to the knee can be caused by a number of factors, such as osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, biomechanical problems, and meniscal tears. Any form of irritation can lead to swelling due to excess synovial fluid production, and if this causes sufficient pressure, it can lead to a cyst forming at the back of the knee. The cyst may or may not cause pain and/or restricted range of knee motion.

This is also known as a baker’s cyst. Irritation to the knee can be caused by a number of factors, such as osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, biomechanical problems, and meniscal tears. Any form of irritation can lead to swelling due to excess synovial fluid production, and if this causes sufficient pressure, it can lead to a cyst forming at the back of the knee. The cyst may or may not cause pain and/or restricted range of knee motion.

Assessment is important in order to differentiate from a tumour or deep vein thrombosis. Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment to find the cause – possibly osteoarthritis or a cartilage leak – and treatment can include: RICE (depending on the cause) and occasionally surgery.

Do you have a gradual onset of knee pain on the inner side, plus limited range of movement, especially when it comes to bending? Is the knee stiff on rest?

If so, you may have osteoarthritis, and you are more likely to suffer from this if:

- You’re in your late 40s or older – your muscles have become weaker, your body is less able to heal itself, and your knee joints have gradually worn out over time.

- You’re a woman – osteoarthritis is more common and more severe in

- You’re overweight – this increases the chances of osteoarthritis and of it becoming gradually worse.

- Your parents or siblings have had osteoarthritis.

- You’ve had a knee injury – for example, a torn meniscus.

- You’ve had an operation on your knee – for example, a meniscectomy (to remove damaged cartilage) or repairs to your cruciate ligaments.

- You do a repetitive activity or have a hard, physically demanding job, like a physio.

- You have another type of joint disease that has damaged your joints – for example, rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

- See more at: http://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/arthritis.

Main symptoms can include pain (in the knee, or at the end of the day – this usually gets better when you rest), stiffness (especially after rest – this eases as you get moving), crepitus (a creaking, crunching, grinding sensation when you move the joint), hard swellings (caused by osteophytes, calcified bony growths), and soft swellings (caused by extra fluid in the joint). Other symptoms can include: your knee giving way because your muscles have become weak or the joint structure is less stable, your knee not moving as freely or as far as normal, your knees becoming bent and bowed, the muscles around your joint looking thin or wasted, and the joint looking thickened.

It’s unusual, but some people have pain in their knee that wakes them up at night. This generally only happens with severe osteoarthritis – Grade III or IV. You’ll probably find that your pain will vary, with good days and bad days. This can be due to how active you’ve been, but sometimes it will just happen for no clear reason.

Some people find that changes in the weather (especially damp weather and low barometric pressure) make their pain and stiffness worse, and this may be because nerve fibres in the capsule of their knee are sensitive to changes in atmospheric pressure.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory disease that can strike at any age. When arthritis develops following an injury to the knee, it is called post-traumatic arthritis, and this can occur years after a torn meniscus, injury to ligament, or fracture of the knee. Some types of arthritis can also cause fatigue.

Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory disease that can strike at any age. When arthritis develops following an injury to the knee, it is called post-traumatic arthritis, and this can occur years after a torn meniscus, injury to ligament, or fracture of the knee. Some types of arthritis can also cause fatigue.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic disease of the immune system, affecting multiple joints in the upper as well as the lower limbs. Knees are one of the most common joints affected by RA, which can occur at any age and which can affect both knees. When RA affects the knee joint, the synovium that lines the ends of the bones thickens and produces an excess of joint juice – it is said to feel like a crisp packet. The immune system supplies inflammatory juices, leading to swelling and damage to the cartilage that normally acts as a cushion within the joint. This then leads to pain and joint erosion.

Symptoms of RA mostly include pain and stiffness of the affected joints, and the pain is more often than not worse in the mornings, a time that is associated with severe stiffness. The joint may become stiff and swollen, making it difficult to bend or straighten the knee, and pain and stiffness is also at its worst after a period of inactivity. The knee may feel weak, it may feel ‘locked’, or it may ‘buckle’ as a result of this disease. Due to inflammation, blood tests such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be raised. These are, however, non-specific markers of inflammation as it is not straight forward to diagnose. Rheumatoid factor is a relatively specific test, and there is presence of this indicative factor in nearly 80% of all rheumatoid arthritis sufferers. Presence of rheumatoid factor may NOT be detected in early stages of the disease. In addition, just to really f*** up the diagnosis, around 1 in 20 healthy persons may test positive for rheumatoid factor (RF), hence RF is not absolutely indicative of rheumatoid arthritis.

Several imaging studies such as X-rays, MRI scans, and CT scans may be ordered to look at the extent of joint damage caused by the disease; X-rays typically show a loss of joint space in the affected knee. To ease the symptoms, pain relievers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used widely to control the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. They are, however, notorious for their side effects due to which they may be used for a short-term basis only. A healthy diet and supplements can also help.

To prevent progression of joint damage, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are used. They act by reducing joint swelling and pain, decreasing markers of acute inflammation in the blood, and halting the progressive joint damage. DMARDs include Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine, Leflunomide, Hydroxychloroquine, Gold salts and Cyclosporine. However, everything comes with a price and these are also associated with a varying degree of side effects.

CORTICOSTEROIDS

Corticosteroids are anti-inflammatory agents that may be given as medications or as injections directly into the joint spaces in order to reduce the joint inflammation. I have given these jabs in the past.

BIOLOGICAL AGENTS

A newer approach is to use biological agents such as TNF (tumour necrosis factor), cytokines that kill cells you do not want.

SUPPORTIVE TREATMENT

Supportive treatment includes exercise prescription, physiotherapy, joint protection nutrition, psychological support, and a multitude of alternative medicines.

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS

Lifestyle modifications include losing weight, and changing exercises from running or jumping to swimming or cycling – things that don’t carry the risk of damaging the knees. Weight loss can reduce stress on weight bearing joints, such as the knee.

PHYSIOTHERAPY

Physiotherapy is an important part of the treatment of debilitating arthritis, as it helps maintain optimum joint flexibility and strength. Assistive devices – such as a cane, walker, long shoehorn etc. – may help cope with disabilities associated with knee rheumatoid arthritis.

SURGERY

Surgery may be performed to retain joint function or prevent the loss of joint function. Joint replacement therapy may also be chosen, which is vital when joints fail. There are different types of surgery to correct different joint problems, and total or partial knee replacement is often recommended for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Do you have inner knee pain after a ‘twisting with knee bent’ injury, typically with your foot fixed to the ground? Did you feel ‘something go’ with immediate pain and swelling afterwards?

If so, you may have a medial menisci tear.

MEDIAL MENISCI TEAR

The top of the shin bone (tibia) has a coating of cartilage and then two meniscal cups for the long thigh bone (femur) to move in. The menisci have a number of important roles in the function of the knee, such as spreading the load across the top of the shin bone (tibia), plus helping to both absorb shocks and stabilize the knee.

The top of the shin bone (tibia) has a coating of cartilage and then two meniscal cups for the long thigh bone (femur) to move in. The menisci have a number of important roles in the function of the knee, such as spreading the load across the top of the shin bone (tibia), plus helping to both absorb shocks and stabilize the knee.

The menisci are often torn in knee injuries, particularly those involving twisting while the knee is bent, which is common in many sports. Aggravating factors can include aging, as much of the body’s connective tissue becomes more rigid and less elastic with age.

The menisci have a poor blood supply and often will not heal. Therefore, in cases where conservative treatment does not work, surgery is indicated with either repair or removal of the torn tissue. The top of the shin bone (tibia) has a coating of cartilage and then two meniscal cups for the long thigh bone (femur) to move in. The menisci have a number of important roles in the function of the knee, such as spreading the load across the top of the shin bone (tibia), plus helping to both absorb shocks and stabilise the knee.

The lateral meniscus is less prone to tearing than the medial meniscus and tends to occur with twisting while weight bearing, which is common in many sports. Aggravating factors can include aging, as much of the body’s connective tissue becomes more rigid and less elastic with age. Typical symptoms are significant pain if the knee is rotated, or if a sudden load increase occurs – as in jumping.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and MRI, and treatment can include: RICE, physiotherapy, MBST, gentle specific rehab, knee brace, TENS, laser, ultrasound, sports massage, mobilisations, and surgeon referral. Recovery times will vary widely depending on the grade of injury, and may be several months.

SYNOVIAL PLICA

The knee is encased in synovial tissue, and sometimes a fold (synovial plica) will remain in the tissue from birth. If the plica is sufficiently large it can become irritated during activity and is then more susceptible to injury from direct trauma or overuse. This type of injury is most common on the medial side of the knee and its symptoms can sometimes be confused with a medial meniscal tear or patellar tendonitis.

In most cases, a plica can be treated conservatively, including the use of corticosteroid injections. If the symptoms do not respond, then arthroscopic surgery may be needed.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and treatment can include: RICE, physiotherapy, MBST, rehab and exercises, support, sports massage, and TENS. If there is no improvement, MRI and surgeon referral may be needed.

Have you had a blow to the inside of your knee? Is your knee tender and painful on the outer side, most noticeably on the bone just below the knee?

If so, you may have a problem with your collateral ligaments.

COLLATERAL LIGAMENTS

These are found on the sides of your knee. The medial/inner collateral ligament (MCL) connects the femur to the tibia, while the lateral/‘outside’ collateral ligament (LCL) connects the femur to the thin bone in the lower leg (fibula). The collateral ligaments control the sideways motion of your knee and protect it against sudden movements – the knee joint relies just on these ligaments and the surrounding muscles for stability. Any direct contact to the knee or hard muscle contraction – such as changing direction rapidly while running – can injure a knee ligament. Injuries to the collateral ligaments are usually caused by a force that pushes the knee sideways, and while these are often contact injuries, they’re not always.

Medial collateral ligament tears often occur as a result of a direct blow to the outside of the knee, and this pushes the knee inwards (toward the other knee). If there is an MCL injury, the pain is on the inside of the knee; an LCL injury pain is on the outside of the knee. A blow to the outside of the knee does the latter, and you get swelling over the site of the injury. Injury causes instability, and this is when the knee gives way. Injured ligaments are considered ‘sprains’ and are graded on a severity scale.

-

Grade I sprains: The ligament is mildly damaged. It has been slightly stretched, and is still able to keep the knee joint stable.

-

Grade II sprains: This stretches the ligament to the point where it be-comes loose. It is referred to as a partial tear of the ligament.

-

Grade III sprains: This type of sprain is a complete tear of the ligament. The ligament has been split into two pieces, and the knee joint is un-stable.

Do you have pain just below the knee? Is it painful to extend the knee, and worse after exercise?

If so, you may have Osgood-Schlatter disease.

OSGOOD-SCHLATTER DISEASE

Osgood-Schlatter dis-ease (OSD) – also known as apophysitis of the tibial tubercle, or Lan-nelongue’s disease – is an inflammation of the pa-tellar ligament at the tibi-al tuberosity. It is charac-terised by a painful lump just below the knee and is most often seen in young adolescents.

Osgood-Schlatter dis-ease (OSD) – also known as apophysitis of the tibial tubercle, or Lan-nelongue’s disease – is an inflammation of the pa-tellar ligament at the tibi-al tuberosity. It is charac-terised by a painful lump just below the knee and is most often seen in young adolescents.

Osgood-Schlatter disease describes the local pain in the tendon under the kneecap (patella), which links the kneecap to the top of the shin bone (tib-ia). The tendon becomes inflamed and swollen due to repeated tension whilst exercising, and is most common in early teenage boys, particularly those undergoing a strong growth phase. In some cases the tendon becomes calcified.

Osgood-Schlatter disease occurs most often in children who participate in sports that involve running, jumping, and swift changes of direction – such as soccer, basketball, figure skating, and ballet. While Osgood-Schlatter disease is more common in boys, the gender gap is narrowing as more girls become involved with sports. Age ranges differ by sex because girls experience puberty earlier than boys, so the Osgood-Schlatter disease typically occurs in boys aged 13 to 14 and girls aged 11 to 12. The condition usually resolves on its own, once the child’s bones stop growing; the discomfort can last from weeks to months and may recur until your child has stopped growing.

Provisional diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and X-Ray, and treatment can include: RICE, massage, and a specific rehab program. If severe, casts, patella tendon straps, or braces may be needed.

Do you have pain in the knee on movement? Does the movement feel boggy, and is there swelling?

If so, you may have knee bursitis.

KNEE BURSITIS

A bursa is a sac of synovial fluid that is positioned to cushion joints and help tendons move more freely and with less friction. The overuse of joints and tendons can cause tendinitis and inflammation of the bursa, which is called bursitis. The primary action of the quads is to straighten the leg at the knee, and these four strong muscles all connect to the upper kneecap (patella) through the suprapatellar tendon. Overuse of this tendon – or local trauma – can cause tendinitis and also bursitis of the underlying suprapatellar bursa, plus nearby infrapatellar and prepatellar bursae.

The infrapatellar bursa is located under the tendon connecting the bottom of the kneecap to the shin bone, the infrapatellar tendon. This area is prone to injury from any biomechanical misalignment. Inflammation of the infrapatellar bursa is also known as ‘clergyman’s knee’, as historically, clergymen were prone to this condition due to frequent kneeling. A similar condition occurs with the bursa in front of the kneecap – the prepatellar bursa – known as ‘housemaid’s knee’. Infrapatellar bursitis can often coincide with infrapatellar tendinitis, or jumper’s knee.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, and treatment can include: gentle progressive physiotherapy, training of correct lifting techniques, laser, electrotherapy, MBST, and biomechanical assessment. If non-responding, corticosteroid injections may be used.

Do you have pain in the knee with swelling, creaking, and pain on running? Does your knee feel as if it catches and is unstable?

If so, you may have osteochondritis dissecans.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS

In most cases this affects the knee joint, but it can also occur in other body joints. Osteochondritis dissecans describes the separation of a piece of cartilage, plus a small piece of bone from one of the bones in the joint. This is caused by a local weakening in the bone due to insufficient blood supply and mainly occurs following a trauma to the joint. In some cases surgery may be needed to repair the bone, but in many cases the problem will self heal.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment with orthopaedic opinion, X-ray, and MRI, and treatment can include: RICE, MBST, and physiotherapy. If not healing, surgery may be needed.

Are you tender just above the kneecap, possibly with swelling? Do you get the same pain if someone else bends your knee or if you try to straighten your knee against resistance?

SUPRAPATELLAR TENDON

Overuse of the suprapatellar tendon – or local trauma – can cause tendinitis and also bursitis of the underlying suprapatellar bursa, plus the nearby infrapatellar and prepatellar bursae. This area is prone to injury from any biomechanical misalignment.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, and to confirm, MRI, and treatment can include: gentle progressive physiotherapy, MBST, laser, ultrasound, biomechanical assessment, and training of the correct lifting technique.

CHONDROMALACIA PATELLA

This describes the condition where the back of the kneecap (patella) – which is normally covered in cartilage to provide a smooth, low friction contact with the thigh bone (femur) – is damaged, leading to a painful and sometimes noisy contact. It is more common in women and tends to be more prevalent in under 30’s.

Chondromalacia patella could be caused by a number of factors:

-

Individual knee misalignment problems.

-

Overuse.

-

Poor tracking due to muscle imbalance or hypermobility.

-

Trauma.

-

Normal wear and tear from aging.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, X-ray, scope, and biomechanical assessment, and treatments can include: physiotherapy, MBST, shockwave, sports massage, muscle strengthening, stretching and balancing, orthotics, possible knee support, or taping. If unresponsive, try scope for plica or surgery.

HYPERMOBILITY

This is commonly referred to as being ‘double jointed’, and it is a condition where joints are allowed to move further than in a normal joint. People who have hypermobility tend to be more prone to sprains and strains, and are generally more accident-prone. The implications of hypermobility include:

This is commonly referred to as being ‘double jointed’, and it is a condition where joints are allowed to move further than in a normal joint. People who have hypermobility tend to be more prone to sprains and strains, and are generally more accident-prone. The implications of hypermobility include:

- More rapid muscle fatigue as muscles have to compensate for joint laxity.

-

More muscle pain than normal.

-

Greater prevalence to childhood growing pains.

-

Increased joint wear and tear and hence early onset osteoarthritis.

-

More easily dislocated joints, especially in the shoulder.

-

Prone to lower limb joint pain.

-

Increased risk of spinal disc bulge and spondylolisthesis.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment and/or a rheumatologist, and treatment can include: orthotics, which can help assist lower limb joint pain.

Is it tender just below your kneecap? Is it painful to contract your quads, or after exertion?

If so, you may have infrapatellar tendinitis.

INFRAPATELLAR TENDINITIS

This condition is also known as jumper’s knee. The straightening of the knee is achieved primarily through the quads and their attachment to the top of the kneecap (patella) with a very strong tendon. This force is transferred through the kneecap down to the lower leg by the infrapatellar tendon, which connects the lower part of the kneecap to the shin bone (tibia). Tendinitis is a condition where the tendon becomes irritated and inflammed. Infrapatellar tendinitis is most often caused by overuse and is particularly common in sports involving repeated jumping, such as football and netball. This condition can often occur with infrapatellar bursitis.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, grading by the severity of pain and swelling, and MRI, and treatment can include: RICE, rest from aggravating activities, gentle progressive physiotherapy, sports rehab, laser, ultrasound, and MBST. If severe, a sports surgeon referral may be needed.

Is there tenderness and possible swelling on the outer side of your knee? Is knee movement restricted, and does it hurt to squat?

Is your knee tender on the inner side around the joint line?

As covered earlier, the inner side of your knee could be tender for a number of reasons, but most likely, it is a sprain to the medial collateral ligament (MCL). This is a common injury in skiing and contact sports, and comes in grades I to III.

-

Grade I: Mild sprain.

-

Grade II: Partial tear.

-

Grade III: Complete rupture and the knee feels unstable.

COLLATERAL AND CRUCIATE LIGAMENT COMBINED INJURY AND MEDIAL MENISCI TEARS

Was there an audible crack at injury? Does the knee feel unstable, and does the pain feel deep in the knee? Is it warm and swollen?

Is swelling pronounced within 24 hours, and does it feel thick rather than fluid? Is it painful at the end range of movement of your knee?

If so, you may have a combined injury.

The knee is stabilised by four major ligaments: not just the collaterals, but also the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligaments (PCL). The medial collateral ligament (MCL) connects to the femur (the long thigh bone) and the tibia (the shin bone), its task being to stabilise the inside of the knee (medial) and prevent it from opening up. However, it can be damaged in conjunction with the ACL. The MCL is most often injured when the outside of the knee is struck from the side, and depending on the amount of force, this will overload the MCL to cause anything from a mild sprain to complete rupture. This is a common injury in skiing and contact sports. Often, an MCL injury coincides with an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury or a meniscal tear, and can injure both the medial and lateral coronary ligaments. This type of injury is common to football.

Grade I and II injuries will be painful over the ligament and will result in swelling within one or two days. With a full thickness tear – grade III – the knee will feel unstable and it will be difficult to bend it. Grades I and II will

require ceasing the sport for one to four weeks, whereas a grade III tear will need bracing for at least six weeks. Surgery is not often needed.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, specific test for grading I to III, MRI if a suspected grade III, and sports surgeon consultation. Treatment can include: RICE, physiotherapy, rest from training, knee brace if grades II or III, sports massage, ultrasound, pulsed shortwave, laser, MBST, and rehab that includes proprioception work for rough ground. Full recovery only comes with rehab.

CRUCIATE LIGAMENTS ACL AND/OR PCL SPRAIN

To reiterate, the knee is stabilised by four major ligaments, the medial (MCL) and lateral (LCL) collateral ligaments, and the anterior (ACL) and posterior (PCL) cruciate ligaments. The ACL and PCL lie deep within the knee joint, and of these, the ACL

is much more prone to injury in sport, typically with a non-contact rapid deceleration whilst running or a twisting fall. This may also coincide with a MCL and medial meniscal injury. If the pain is behind the knee, it is more likely PCL.

PCL injuries are most common when the knee is bent and the shin is forced backwards – this is common in car accidents or in sports when a player lands hard on the knees with the knees fully flexed.

Diagnosis is by physiotherapy assessment, MRI, endoscope, and X-ray, and treatment can include: RICE, stopping the sport, physiotherapy, MBST, brace, rehab and exercises, and possible surgeon referral and prescribed pre-surgery rehab.